Clarity Law

Jacob Pruden

Jacob is a former barrister and now criminal defence lawyer with over 8 years experience appearing in courts throughout South East Queensland representing clients charged with criminal offences.

Going to Trial in the Magistrates Court

In the Queensland system of criminal justice, once a person is charged with criminal offences there are broadly three ways the charges get resolved: a plea of guilty, the prosecution withdraw the charges, or a trial. This article will be about trials, so strap in, there is a lot to cover.

How do I know when I should go to trial?

Our article titled “Deciding How to Plead to a Criminal Offence” covers this well, but the short version is, if you did not commit the offence, or the prosecution cannot prove you did, you should take it to trial.

Why would my case go to trial in the Magistrates Court instead of another court?

Legally, most charges and cases are decided in the Magistrates Court. The more serious offences, such as drug trafficking, grievous bodily harm, and rape, will be heard in higher courts. Some charges can be heard in either the Magistrates Court or higher courts, but we need not go into that here.

Charges that stay in the Magistrates Court are still considered serious. People are routinely sentenced to jail in the Magistrates Court, and the court can impose a maximum of three years imprisonment.

Where you have the option of having your trial heard in the Magistrates Court or higher courts, there are a number of factors to consider, including cost, delay, whether you want a jury, and the maximum penalty.

How do I get to a trial in the Magistrates Court?

By entering a plea of ‘not guilty’ in court. The magistrate marks this down on the court file, and then a number of things happen.

First, the police must produce a full brief of evidence. This will contain witness statements and exhibits such as video footage, photographs, and forensics.

Second, once your solicitor receives the full brief of evidence, he or she will analyse it to determine whether the prosecution can prove their case, will take your instructions on what happened, and then give advice about likely outcomes.

Third, based on the advice given by your solicitor you will make decision whether you wish to persist with the trial, send a submission or change your plea to guilty. If the plea remains not guilty, then the case will have a date in the Magistrates Court for your trial.

What happens at a trial?

On the day of the trial [most trials in the Magistrates Court take only one day], the magistrate will listen to and view the evidence, and decide whether you are guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

It is the prosecution who must prove your guilt. They must do this beyond reasonable doubt, which means it’s not sufficient for the magistrate think that you are possibly, or even probably guilty, but he or she must have no reasonable doubt about it.

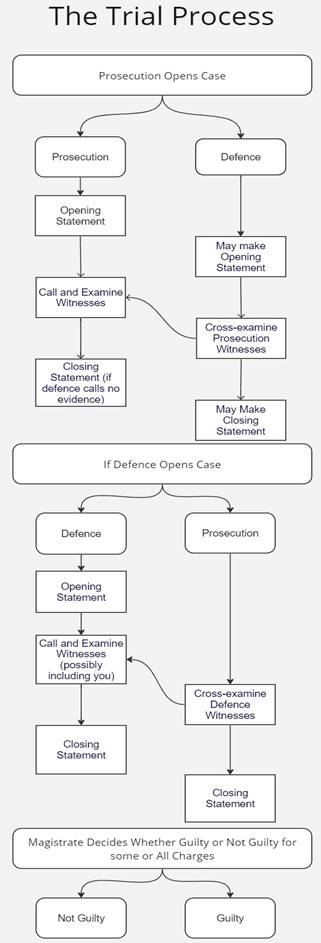

How does the trial proceed? I have created a chart which I hope will assist you to visualise how it happens in court:

Will I need to give evidence or speak in court?

The answer is maybe. You have a legal right to silence, which means you are not obligated to give evidence in support of your defence.

You might have given a recorded interview to police, in which case, your version of events may already be available without the need to speak in court.

There are disadvantages to telling your story in court, including: the prosecutor gets the opportunity to cross-examine you, you might get flustered and accidentally say something which hurts your case, or what you say might be inconsistent with something you've said prior [such as if you had given a police interview].

In general, if it looks like the prosecution are unable to prove their case on the evidence they have presented, then it would usually be the right call not to give evidence. If, however, the prosecution do look like they are able to prove their case, and the credibility and reliability of prosecution witnesses has not been damaged enough by your lawyer’s cross -examination of them, your best option may be to give evidence yourself to have a chance of winning the trial.

But the witnesses have lied! Surely I will be found not guilty?

Although the stated purpose of the trial process is to discover the truth of what happened, the reality is that the magistrate is presented with two different arguments about what happened: one from the prosecution, the other from the defence. It may well be the case that one or more witnesses lie in their testimony. Hopefully, in that situation, a lying witness will have had their credibility forcefully challenged when questioned by defence counsel.

It is important to keep in mind that each case, the prosecution and the defence, is designed to persuade the magistrate to reach a certain conclusion, and this may not necessarily be in perfect alignment with what really happened. As the saying goes, “there are two sides to every story”.

Whay happens at the end of the trial?

The magistrate decides whether you are guilty or not guilty. If you are found guilty, usually the sentence will proceed immediately. The main disadvantage with losing a trial is you should expect a harsher penalty than you would have gotten had you pleaded guilty.

If you win the trial, this is called an acquittal. This means the charge against you is dismissed, and there is no penalty.

Can I get costs?

If you win, you can argue for costs. There is a legal test the magistrate must follow to decide whether costs should be granted in your favour. Bear in mind, there is a limit to the amount of costs the magistrate can order in your favour, and you would not recover the full amount of your legal fees.

Conclusion

As you can see, Magistrates Court trials are complicated, and the decision whether to go to trial is often a difficult one. If you or someone you know is in such a situation, you need expert legal advice. All Clarity Law’s solicitors are fully qualified and experienced. We can help you to make the best choice for your situation.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further free information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email the firms founder on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission or until we are legally allowed to.

Charge of engaging in intercourse with a child under 16

Introduction

This offence, which used to be called “Carnal Knowledge of a child under 16”, is relatively self-explanatory, being that a person has penetrated a child’s vagina, vulva or anus with “the person’s” penis.

Under what law is the offence?

This offence is under section 215 of the Queensland Criminal Code Act.

Legal Elements

The Supreme and District Courts Criminal Directions Benchbook states the legal elements of the offence as:

-

The prosecution must prove that there was an act of penile intercourse.

-

The intercourse was of the vagina/vulva/anus of another person.

-

The person was under 16 years.

Meaning of engage in penile intercourse:

-

Penile intercourse is the penetration, to any extent, of the vagina, vulva or anus of a person by the penis of another person.

-

A person engages in penile intercourse with another person if—

-

The person penetrates, to any extent, the vagina, vulva or anus of another person with the person’s penis; or

-

The person’s vagina, vulva or anus is penetrated, to any extent, by the penis of another person.

Some things to note about the legal elements

-

The prosecution does not need to prove a lack of consent. It is legally irrelevant whether or not the complainant consented.

-

The prosecution need not prove that the defendant knew the complainant was younger than 16.

-

The definition of penile intercourse curiously substitutes masculine phrasing such as ‘his penis’ and ‘penis of a man’ with ‘the person’s penis’ or ‘the penis of another person’. One might speculate this is worded to capture occasions where ‘the person’ has a penis, but ‘identifies’ as female or non-binary.

Penalty

The maximum penalty for this offence is 14 years.

The Penalties and Sentences Act states that a person charged with this offence must serve an “actual term of imprisonment, unless there are exceptional circumstances.” The law allows a court to have regard to closeness in age between an offender and the child. For example, an age gap of 15 and 19 is obviously more favourable to a defendant than 14 and 40. But closeness of age is only one factor for the court to consider.

The consent of the child is not sufficient, of itself, to constitute exceptional circumstances.

Possible circumstances of aggravation

A circumstance of aggravation is something that can be alleged by the prosecution as an additional aspect to the charge that makes it more serious at law.

-

For a circumstance of aggravation of the child being under the age of 12 years, the maximum penalty increases to life imprisonment.

-

If the offender was the child’s guardian (but not of lineal descent) or the child was under the offender’s care, the maximum penalty increases to life imprisonment.

-

If the child is a person with an impairment of mind, the maximum penalty increases to life imprisonment.

Defences

If the offence is alleged to have been committed against a child of or above the age of 12, it is a defence to for the accused person to prove that he believed, on reasonable grounds, that the child was of or above the age of 16 years.

The onus of proving the defence is on the defendant, on the balance of probabilities.

Section 229 of the Code expressly states it is immaterial that the accused person did not know that the person was under that age, or believed that the person was not under that age. Because of s 229, a defendant cannot raise a defence concerning the age of the complainant based on the defence of ‘honest and reasonable mistake fact’ , which would leave the onus of proof on the prosecution.

Which Court hears the Charge?

The matter starts in the Magistrates Court and then is committed to the District Court. Thus, any trial on this charge would be heard by a judge and jury.

Conclusion

Needless to say, charges of this kind are taken very seriously by the courts and the community. Should you find yourself accused of such a crime, it is absolutely vital you seek expert legal advice to assist you in getting the best outcome possible. We at Clarity Law are criminal and traffic law experts, experienced in defending such charges.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further free information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email the firms founder on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission or until we are legally allowed to.

How can I Change my Bail Conditions?

A person charged with a criminal or traffic offence in Queensland may be placed on bail. In many instances the only condition of that bail will be for the person to return to court on a designated date. However, some offences, especially more serious ones, will come with additional bail conditions. This article is not a general guide for bail, but you can find such articles here.

Navigating bail conditions in Queensland can be challenging, especially for serious offences. While some bail conditions are straightforward, others can be quite restrictive. Understanding your rights under the Queensland Bail Act is crucial. If your bail conditions seem too harsh or unnecessary, you have the right to apply for a change. At Clarity Law, our experienced team can guide you through the process, ensuring your conditions are fair and manageable.

What the Bail Act says

The Queensland Bail Act says a court, or police officer, must not make conditions for a grant of bail more onerous than necessary for the person seeking bail, having regard to the nature of the offence, the circumstances of the defendant and the public interest.

As noted in the Bail Benchbook, the Bail Act provides the magistrate with very broad powers to impose special conditions, as the magistrate sees fit, provided the magistrate considers the imposition of the special conditions are necessary to:

- Secure the defendant’s future appearance,

- Ensure the defendant, while he or she is on bail, does not:

- Commit an offence,

- Endanger the safety or welfare of members of the public,

- Interfere with witnesses or otherwise obstruct the course of justice.

What is the legal test for a change of bail conditions?

When a defendant is applying to vary his or her bail conditions, a magistrate should consider:

- Whether the conditions of bail imposed originally are still necessary to secure the defendant’s compliance with the matters set out in the above paragraph; and

- Whether those conditions at the time of the application to vary bail are more onerous than necessary, having regard to:

- The nature of the offence,

- The defendant’s circumstances,

- The public interest.

What kind of bail conditions can a court impose?

Take as an example a person charged with drug trafficking. The conditions may include:

- You are to live at address X unless permission to change the address is given by the officer in charge of Maroochydore police station or an officer of the DPP.

- You are not to associate with person X.

- You must give details of any mobile device you use to police or and officer of the DPP.

- You must undertake drug counselling with two months on release on bail, or, failing that, provide a reasonable explanation to the officer in charge of the Maroochydore police station why you are yet to do so.

- You must report to the Maroochydore police station every Monday, Wednesday and Friday between the hours of 8am and 4pm.

- You are subject to a curfew. You must answer the door to a member of the Queensland Police Service, as required, between the hours of 9pm and 6am.

How do I change my bail conditions?

Most of the time this would require an application to the court that granted bail to amend the current bail conditions. In some cases the current bail may allow a senior police officer or the DPP to change a bail condition for example the police often have the power to change the address the person might have to reside at. Always seek legal advice on the best way to change a bail condition as a failure to comply with the bail conditions can lead to charges of breaching bail and the possibility the bail is revoked and the person remanded into prison.

Conclusion

As can be seen, bail conditions can be strict and can substantially interfere with a defendant’s life. However, bail conditions can not be imposed without reason, and if they appear too onerous or not fit for purpose, you can make an application to change them. You would undoubtedly be greatly assisted in this by engaging a solicitor. We at Clarity Law are criminal and traffic law experts, and can assist you with all aspects of a case, including bail applications and changing bail conditions.

The police want to talk to my child about an offence

Introduction

It is always a highly stressful situation when police want to talk to your child about an offence. This article will hopefully give you a brief overview of the factors to consider in Queensland.

Should my child talk to police?

The answer is ‘maybe’.

The case for ‘no’.

A defence solicitor’s reflexive advice is often to tell a suspect to give a ‘no comment’ interview. What this means is, the person tells police (either personally or through a solicitor) that they do not want to answer any questions in an interview. If police ignore this and try to plough on with an interview anyway, that interview would not be allowed to be used as evidence against the person.

People are sometimes concerned that not speaking to police will make things worse for them. However, the law specifically says a person is not to be punished simply for refusing to speak to police or incriminate themselves. This is called the ‘right to silence’.

Police approaches to interviews will generally be friendly, with such comments as ‘I just want to hear your side of it’ or ‘I’m just trying to figure this thing out and I am hoping you can help me’. This gives the suspect the illusion he is being helpful and the police want to help him, when in reality he is just giving police more ammunition to use against him. When a person is suspected of criminal offending by police, honesty is usually not the best policy.

The case for ‘yes’.

The case for children is different from adults. The law says that if a child gives a confession, then police should consider other options besides prosecution. However, if the child refuses an interview, then the police are left with no option but to bring charges.

The Queensland Police Operation Procedures Manual states “where a prima facie case is established against a child in relation to an offence, officers should, wherever practicable, divert the child from the court system, unless the nature of the offence and the child’s criminal history indicate a proceeding for the offence should be commenced.”

The Manual identifies that police must consider alternatives to commencing court proceedings, including:

-

taking no formal action,

-

administering a caution,

-

referring the matter to a restorative justice process,

-

offering the child the opportunity to attend a drug diversion assessment program (for a drug related offence),

-

for an offence of being intoxicated in a public place, take and release the child at a place of safety.

Importantly, for the purposes of this article, the Manual says:

Before a caution or other diversion action can be taken against a child, the child must:

-

admit to committing the offence to the police officer and

-

consent to the caution or other diversion action.

If a child does not admit to the offence, diversion options are not available.

In other words, for a child to avoid being charged and having the matter sent to court, the child must admit to committing the offence. This is obviously relevant to an interview, because if the child refuses to take part in an interview, then diversion options such as cautions are not available to the police.

Obviously, if your child did not commit an offence, he or she should not be admitting to it.

It still may be a bad idea to give an interview.

Although police are required to consider alternatives to formal prosecution when a child admits an offence, they are not obliged to avoid formal charges. If the alleged offence is serious or the child already has criminal history, they may proceed to prosecution anyway. Then, a confessional interview has most likely hurt, rather than helped.

For example, if a child is suspected of a home invasion, armed robbery, or other serious offence, even if it is her first interaction with police, police are likely to prosecute even if the child admits the offence. Likewise, police tend to charge drink and drug driving offences for children, even those with no traffic history.

So, what should you do?

As can be seen, whether your child should speak to police is really guided by the particular circumstances of his or her alleged conduct. A overview like this can only ever be general in nature, and that is why it is important to get expert legal advice so we can consider all the relevant information, and potentially speak to police about the matter. If the police contact you about wanting to talk to your child ring a lawyer before you do anything.

Disclaimer

This article is an outline and is not legal advice. If police want to speak to you or your child about an alleged offence, please seek legal advice from a solicitor who specialises in criminal law. Also this article only applies to the situation in Queensland.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further free information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255 seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click here to select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email the firms founder on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission or until we are legally allowed to.

What is the sex offender register in Queensland

Many people may have heard the term ‘registered sex offender’. But what does this mean in Queensland?

The Child Protection (Offender Reporting and Offender Prohibition Order) Act 2004 provides a statutory framework for the supervision of ‘reportable offenders’ in the community. The Act states that any risk to the lives or sexual safety of any children is unacceptable.

The purposes of the Act are therefore to provide for the protection of the lives of children and their sexual safety, and to require offenders who commit sexual, or other serious offences against children, to keep police informed of the offender’s whereabouts and other personal details after the offender’s release into the community.

The law was recently changed in this area (2023) to make reporting requirements more stringent as well as increase the length a reportable offender must report for.

The sex offender register is legally called the “child protection register”. The register is administered and enforced by the Queensland Police Service.

How does a person get on the sex offender registry?

According to the Child Protection (Offender Reporting and Offender Prohibition Order) Act 2004, to get on the register, a person must be a ‘reportable offender.’

A reportable offender is a person who is:

-

Sentenced for a “prescribed offence”,

-

Sentenced for an offence other than a prescribed offence and the court nevertheless makes a reportable offender order against the person,

-

An existing reportable offender.

A reportable offence is:

-

An offence against certain provisions of the Classification of Computer Games and Images Act 1995,

-

An offence against certain provisions of the Classification of Films Act 1991,

-

An offence against certain provisions of the Classification of Publications Act 1991.

The above offences are all related to selling, producing, exhibiting, or possessing material which contains depictions of children in an abusive or exploitative manner.

Further reportable offences under Queensland Criminal Code are:

-

Indecent treatment of children under 16.

-

Owner etc. permitting abuse of children on premises.

-

Engaging in penile intercourse with child under 16.

-

Using internet etc. to procure children under 16.

-

Grooming child under 16 years or parent or carer of child under 16 years.

-

Taking child for immoral purposes.

-

Involving child in making child exploitation material.

-

Making child exploitation material.

-

Distributing child exploitation material.

-

Possessing child exploitation material.

-

Administering child exploitation material website.

-

Encouraging use of child exploitation material website.

-

Distributing information about avoiding detection.

-

Producing or supplying child abuse object.

-

Possessing child abuse object.

-

Repeated sexual conduct with a child.

-

Attempt to commit rape.

-

Assault with intent to commit rape.

-

Sexual assaults.

There is also a long list of offences under Commonwealth law which are, in some way, connected with child abuse offences.

In short, offences which are classified as reportable offences are related to sexual abuse of children, or possession/production of material that depicts sexual abuse of children.

How does the register work?

Once a person is classified as a reportable offender, they are required to disclose the following information to the government:

-

Their name,

-

Date and place of birth,

-

Details of an tattoos or permanent distinguishing marks,

-

Any premises where the reportable offender generally resides.

If the person has had contact with a child, details known to the reportable offender about the child and the nature of the interaction.

If employed:

-

The nature of the employment,

-

If the offender is employed by an employer—the name of the employer,

-

The address or locality of each of the offender’s usual places of employment.

Details of any club or organisation of which the reportable offender is an associate, employee, member, official or subordinate that has child members or organises, supports or undertakes activities in which children participate.

The make, model, colour and registration number of any vehicle the reportable offender owns and has driven on at least 7 days within a 1-year period, whether or not the days are consecutive.

Details of any:

-

Mobile phones,

-

Electronic devices (such as iPads),

-

Email addresses,

-

Computers,

-

Social media platforms.

Details include such things usernames and passwords, telephone numbers, email addresses and models of electronic devices,

The passport number and country of issue of each passport held by the reportable offender.

How long must a person be on the register for?

Prior to April 2023

-

A person who commits reportable offence must report for five years.

-

The offender must report for 10 years if the offender was already subject to reporting obligations and commits one further reportable offence.

After April 2023

-

10 years for one or more offences dealt with at the same time.

-

The offender must report for 20 years if the offender was already subject to reporting obligations and commits one further reportable offence.

-

The offender must report for life if the offender was already subject to reporting obligations and commits multiple subsequent reportable offences.

Offences under the Act

The main offence is “failure to comply with reporting obligations” which can be penalised by a fine of up to a maximum of $47,000 or imprisonment for a maximum of five years.

It is a defence to prove the person had a reasonable excuse for failing to comply.

Conclusion

As can be seen, the register imposes onerous obligations to those who are required to report. It is important for any person who may be subject to the reporting legislation to understand their obligations. It is also important for any person charged with a ‘prescribed offence’ to get expert legal advice as to how he or she may be affected.

Disclaimer

For purposes of brevity, not every single instance of when a person can be placed on the register has been identified, nor has every offence or every condition of reporting obligations been identified. Please consider this article to be an outline of the legislation only. It is not legal advice, nor should it be considered a substitute for legal advice specific to your circumstances.

When are you required to give police your name and address?

Queensland Police can, unsurprisingly, exercise a wide variety of quite coercive powers. We all know police can arrest and detain people, seize evidence related to crime, and compel people to provide information. These powers are all necessary so police can carry out their important function of investigating unlawful conduct and charging suspects.

What people may not know is police power is not unlimited, and there are important safeguards in place to ensure police know the limits of their powers and do not exceed them.

A police officer may require you to state your correct name and address in prescribed circumstances.

The police officer may also require you to give evidence of the correctness of the stated name and address if it would be reasonable to expect you to be in possession of evidence of the correctness of your name or address or to otherwise be able to give that evidence.

So when can police ask for my name and address?

The prescribed circumstances in which police can require you to state your name and address in Queensland are as follows—

-

a police officer finds you committing an offence;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have committed an offence;

-

a police officer is about to take—

o your fingerprints; or

o a DNA sample from you;

-

a police officer is attempting to enforce a warrant, forensic procedure order or serve on you—

o a forensic procedure order; or

o a summons; or

o another court document;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have been or are about to be involved in domestic violence or associated domestic violence;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you may be able to help in the investigation of—

o a domestic violence or associated domestic violence; or

o a relevant vehicle incident;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you may be able to help in the investigation of an alleged indictable offence because you were near the place where the alleged offence happened before, when, or soon after it happened;

-

you are in control of a vehicle that is stationary on a road or has been stopped;

-

a police officer is about to give, is giving, or has given you a police banning notice;

-

a police officer is about to give, is giving, or has given you—

o a public safety order;

o a restricted premises order;

o a fortification removal order;

-

a police officer reasonably suspects you have consorted, are consorting, or likely to consort with 1 or more recognised offenders.

If a police officer is speaking to you and you do not know or understand why, you are entitled to ask the officer the reason for speaking to you and if the officer is requesting your name and address, you may ask the reason for that, too. But, if you are given an answer other than “because I said so” it is best to comply, as you can be charged with an offence of contravening a direction or requirement of a police officer. It is a fine only offence.

You are entitled to ask a police officer to provide his or her name, rank and identification number. You may ask a police officer to record an interaction the officer is having with you, or you may wish to record the interaction yourself.

If police ask you questions which you believe are in connection with an offence in which you are a suspect, you have a right to refuse to answer those questions and seek legal advice.

Conclusion

As can be seen, there are a wide variety of circumstances where police may ask you your name and address, but it is important police explain why such details are required. There all sorts of reasons why police interact with the public, and the taking of your details will generally go no further than taking a note in a notebook. If you are subsequently charged, it is strongly recommended you contact a lawyer, and you should certainly contact a lawyer before any proposed interview.

How long do criminal convictions stay on my record?

When a court finds someone guilty of an offence that court has a discretion whether to record a conviction or not. In that case, the Court will consider, according to the provisions of section 12 of the Penalties and Sentences Act, whether or not to do so. If the Court does not record the conviction, then it will not appear on a standard police check.

This short article, however, is more concerned with how long a conviction will stay on your record if a conviction is recorded or in other words when is a conviction “spent” in Queensland?

To find that out, we look at the Criminal Law (Rehabilitation of Offenders) Act 1986.

The rehabilitation period

The act refers to a ‘rehabilitation period’, which means a person need not disclose, or agencies (such as police) must not disclose, a previously recorded conviction after a certain period, as explained below.

How long will a criminal conviction in the Magistrates Court last?

The rehabilitation period for a summary offence, that is, an offence dealt with in the Magistrates Court, a conviction will not remain visible on your record 5 years from the date of the conviction. This is so long as no other offences have been committed in the meantime.

How long will a criminal conviction in the District or Supreme Court last?

The rehabilitation period for an indictable offence, that is, an offence dealt with in the District or Supreme Court, a conviction will not remain visible on your record 10 years from the date of the conviction so long as no other offences have been committed in the meantime.

Will the fact I was sentenced to prison affect the time the conviction remains on my record?

Possibly, a conviction will remain on your record forever if you were sentenced to a term of imprisonment for the offence, with time actually served. Otherwise, where you have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 30 months or less.

What exceptions to the normal rules exist?

There are multiple other exceptions however with some listed below:

-

A conviction will still appear on your criminal history if relevant for a criminal or civil court proceeding. For example if you go to court for a new criminal charge the court can get access to all your previous convictions.

-

If restitution was ordered then if it has not been paid by the time the rehabilitation period ends the conviction remains until the rehabilitation has been paid in full.

-

It is likely that it would still be required for you to disclose an excluded conviction if you were to apply for Australian citizenship or a blue card.

-

An excluded conviction may still be disclosed if you are seeking admission to a profession, occupation, or calling prescribed by regulation. For example, a lawyer, police officer or corrective services officer.

-

All previous convictions would remain in law enforcement databases.

-

For commonwealth offences where the sentenced occurred in Queensland the rehabilitation period is 10 years no matter which court heard the charge.

In conclusion, the law allows some scope for prior convictions to be hidden from your record.

I had a conviction 15 years ago and I don’t have to disclose it but I’m applying to be a teacher and the form says I must disclosure all convictions

The law specifies where a person must still disclosure a conviction no matter what. They can include:

-

a person applying to be a teacher

-

a person applying to be a lawyer

-

a person applying to be a police officer

-

a person applying for a blue card

You can click here to see the full list.

Can I apply to expunge my conviction early?

No, there is no way to speed up the process and get the conviction removed before the rehabilitation period has ended.

The only rare exception is for people with historical convictions for homosexual offences prior to 1991.

So after the rehabilitation period has ended can I say I was never convicted of an offence?

You can generally say you have no convictions if you meet all the following (see also the exceptions above):

-

you weren't sentenced to imprisonment as part of your sentence or you were sentenced to prison for less than 30 months (regardless of whether you actually had to go to prison)

-

the rehabilitation period (5 years for Magistrates Court convictions, and 10 years for District and Supreme Court convictions or commonwealth convictions) has expired

-

you haven't broken the law since your conviction

-

you have paid any restitution ordered

Remember if no conviction was recorded at the time of the offence then the offence does not appear on your criminal record ever. This article is just about where a conviction was recorded.

Going armed so as to cause fear

This article is all about the Queensland charge of going armed so as to cause fear charge.

The Law

This offence is contained in section 69 of the Criminal Code. The section states:

“ Any person who goes armed in public without lawful occasion in such a manner as to cause fear to any person is guilty of a misdemeanour, and is liable to imprisonment for 2 years.”

The three key ingredients, then, are that:

-

the defendant was in public,

-

openly armed,

-

in a manner likely to cause fear.

In practical terms, the circumstances are important. A person holding a cricket bat in his yard playing a game with his kids is very different from the same man holding a cricket bat in a neighbour’s driveway, calling the neighbour out for a confrontation.

Lawful occasion

It may be noticed in subsection (1) that the person must go armed in public “without lawful occasion”. A person might readily contemplate a “lawful occasion” to be an armed police officer or security guard. For a private citizen there might be lawful occasions to be armed. It is unlikely for self-protection or self-defence to be such an occasion when there is no clear and present threat to the defendant.

One case that considered this question of “lawful occasion” was one where a man, who was on his own property, shot his rifle into the air to break up a fight. One of the judges in the case commented:

Other lawful reasons or excuses for going, at least temporarily, armed in public on the outskirts of towns in western Queensland can readily be imagined. Using a rifle to shoot a rabid dog or a wild pig that presents a threat to the safety of people in the area would surely not under s. 69(1) be “without lawful occasion” simply because it takes place in public and causes fear. Here it was not dogs or pigs that Mr Bennett was seeking to restrain, but his own sons, who were engaged in a serious attack on another person. Firing a shot harmlessly in the air in order to bring them to their senses was not only a legitimate reason or lawful excuse for his going armed in public (if that is what he did) but a thoroughly effective one. On hearing the shot fired, Lindsay decided to “cut it out”, as he said, and leave his victim go. Both he and George stopped hitting Barry Facer and returned to the house.

Defences to the charge of going armed so as to cause fear

-

The defendant was not the person who committed the offence

-

The defendant was not in public

-

The defendant was not “armed”

-

The defendant did not act in a manner to cause fear

-

The defendant had a lawful occasion to be armed

Penalty

The maximum penalty is up to 2 years imprisonment.

Penalties can vary widely for this offence. In one case, a man was sentenced to a term of actual imprisonment for pointing a handgun at someone and pulling back the top slide. Though he didn’t shoot the weapon, the court found his actions to be so serious to be deserving of imprisonment. In another case, a man was brandishing a knife in a threatening way. He was also sentenced to imprisonment. Fines or penalties less than imprisonment are also available for this offence. Nevertheless, the courts consider this to be a serious charge and we highly recommend you seek legal advice if you are charged with such an offence.

Which court hears the charge of going armed so as to cause fear

The Magistrates Court closet to where the alleged offence occurred will hear the charge.

Can the charge be withdrawn?

Depending on the circumstances it may be possible to negotiate the charge with the prosecutor. This is called case conferencing. For example it might be possible to try and convince the prosecutor that the wounding was excused by law or the medical evidence does not meet the standard for a wounding charge and therefore the charge should be withdrawn.

Will I get a criminal conviction if I plead guilty to the charge?

The answer is possibly. It depends on a number of factors. Only an experienced criminal lawyer can give you advice on the best way to try and avoid a conviction being recorded if you plead guilty to this charge. Note however if imprisonment is part of the penalty then a conviction must be recorded.

Learn more about the difference between a conviction and non-conviction

The police want to talk to me about a going armed so as to cause fear charge

Never ever give an interview to police without first getting legal advice. Even if you are innocent, even if you have a defence you could say the wrong thing and virtually guarantee you will be found guilty of the charge.

The police are not on your side, get immediate legal advice.

Learn more about your right to silence.

I’m not guilty of the going armed so as to cause fear

Still don’t talk to the police. A lawyer would require the prosecutor to give them all their evidence and statements. This is known as the full brief of evidence. Once the brief was received then negotiations with the prosecutor to drop the charge can occur.

Learn more about what to do if accused of a crime you didn’t commit.

How do I get more information or engage you to act for me?

If you want to engage us or just need further free information or advice then you can either;

-

Use our contact form and we will contact you by email or phone at a time that suits you

-

Call us on 1300 952 255seven days a week, 7am to 7pm

-

Click hereto select a time for us to have a free 15 minute telephone conference with you

-

Email the firms founder on This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

-

Send us a message onFacebook Messenger

-

Click the help button at the bottom right and leave us a message

We are a no pressure law firm, we are happy to provide free initial information to assist you. If you want to engage us then great, we will give you a fixed price for our services so you will know with certainty what we will cost. All the money goes into a trust account monitored by the Queensland Law Society and cannot be taken out without your permission or until we are legally allowed to.

Introduction to Liquor Law Infringements

Under Queensland law, the serving of alcohol by business establishments is regulated by legislation, with hefty penalties for non-compliance with the laws. This article will touch on these penalty provisions, rather than the laws with respect to applications for liquor licences.

The Relevant Laws

Liquor Regulation 2002

Liquor (Approval of Adult Entertainment Code) Regulation 2002

Wine Industry Regulation 2009

Offences and Penalties

The liquor laws are enforced by specially appointed police and Office of Liquor and Gaming Regulation investigators. The laws apply to those who sell liquor, whether a licenced premises or even online.

Under the Liquor Act 1992, there are more than 100 offences. They are generally dealt with by way of “on the spot” fines, which can be as high as $3,096 or as low as $309. The higher fines are for such infringements as:

- A manager of a licenced premises selling liquor to a minor.

- A manager of a licenced premises failing to prevent a minor from being in a pokies area.

- A manager of a licenced premises allowing liquor to be supplied to a minor.

- A manager of a licenced premises allowing liquor to be consumed by a minor on the premises.

- Selling liquor without a licence.

- Displaying liquor for sale without a licence.

The lower fines are for such infringements as:

- Failure to comply with Commissioner’s direction to repair ID scanner.

- Licensee fail to keep premises clean or in good repair.

- Fail to obtain approval for premises name change.

- Licensee allow sale, supply or consumption of liquor in car park.

More serious infringements can lead to fines of tens of thousands of dollars and other penalties. For example:

- Allow a disorderly patron to consume liquor: Maximum $77,400.

- Licensee engages in practices or promotions that encourage rapid or excessive consumption of liquor: Maximum $15,480.

- Failure to comply with CCTV conditions: Maximum $15,480.

- Allow intoxicated patron to consume liquor (how many times would this occur each weekend?): Maximum $77,400.

- Selling alcohol without a licence: up to $154,800 and 18 months imprisonment.

In case these eye-watering fines were not enough, the laws also give authorities the power to punish breaches of the Act by forcing a business to limit its opening ours, close its premises, or even cancel its liquor licence entirely.

What If You are Fined for A Liquor Licensing Matter?

An individual or business need not accept an on-the-spot fine, especially in circumstances where operators of the venue or staff had no knowledge of the offence. Offences like “allowing a disorderly patron to consume liquor” raises some subjective questions such as: what is disorderly? What if the person consumed liquor out of sight of staff? What if the person was briefly ‘disorderly’ and then settled down? In ambiguous cases like these it may well be worth challenging a massive fine or licence restriction.

A matter can be challenged in the Magistrates Court. Assuming a solicitor is engaged, this will then open the door to negotiations with the Office of Liquor and Gaming Regulation, with an aim of getting rid of the infringements entirely, or at least reducing the fines. Liquor licences are costly enough as it is (thousands of dollars) without business owners or employees being hit with hefty fines for possibly unintentional infractions.

If you find yourself in such a situation, Clarity Law can help. We are experienced in defending traffic, criminal and regulatory matters. We don’t take Legal Aid cases which means your case will get the attention it deserves.

Will a Criminal Charge Affect a Visa Application?

A foreigner who wishes to visit or remain in Australia must be of good character. Character requirements must be met if a person is to continue holding a visa, apply for a visa, or renew a visa. The Australian Department of Home Affairs manages immigration in Australia, and it is the Minister or her delegates who assess the character requirements as they apply to a visa holder or applicant.

What are the Character Requirements?

The main legislative section that refers to character requirements is section 501 of the Migration Act 1958.

The overarching requirement is for a person to pass a character test. To this end, the government applies a character test to those applying for a visa. The government may also apply the character test to cancel a visa that has already been granted.

One of the key indications of bad character is if a person has a substantial criminal record. A substantial criminal record, among other things, includes being sentenced to a single or combined term of imprisonment of 12 months or more (it does not matter how much time you serve in prison, if any, just that the head sentence was 12 months or more)

Other indicators of bad character include, but are not limited to:

- A person has a proven sexual offence involving a child.

- A person has been convicted of a domestic violence offence or has been subject of a domestic violence order.

- Having regard to the person's past and present criminal conduct and the person's past and present general conduct, the Minister considers the person not to be of good character.

- The Minister believes that, in the event the person was allowed to remain in Australia, there is a risk that the person would:

- engage in criminal conduct in Australia; or

- harass, molest, intimidate or stalk another person in Australia; or

- vilify a segment of the Australian community; or

- incite discord in the Australian community or in a segment of that community; or

- represent a danger to the Australian community or to a segment of that community, whether by way of being liable to become involved in activities that are disruptive to, or in violence threatening harm to, that community or segment, or in any other way.

Significance for Criminal Law

There is no specific section of law that states a person’s visa application or visa status will be affected only by a criminal charge. It is possible, however, that the Department of Home Affairs my consider some allegations serious enough to influence a character assessment prior to a conviction.

Once a person is convicted of an offence, however, this can trigger the cancellation of a person’s visa depending on the nature of the offence, and the extent of the penalty.

If a person is in Australia on a visa and they lodge another visa application, and that application is refused on character grounds, then any current visa is also cancelled.

A cancelation or refusal of a visa can be appealed, if the decision was not made by the Minister personally.

Conclusion

The more serious the criminal conduct, the more likely it will affect a person’s visa status. A person is unlikely to have his or her visa cancelled for a speeding offence or a parking infringement. If the person is charged with a serious offence, however, it would be wise to obtain legal advice regarding the possible implications this may have for the person’s visa status.